A trip abroad is always a good idea. New landscapes bathed in a different light, enticing smells and tastes, a foreign language in the background- as a kaleidoscope of impressions imprints itself in our minds, we tap into one of our innate (and most valuable) qualities: curiosity.

Helen Frankenthaler found her journeys across Europe and the US an important source of inspiration, so to coincide with the start of a prime travelling time, we have followed the artist on some of her trips. Come and join us via this series of posts on a short whistle tour across Spain, Italy and New England as we explore some of the places Helen Frankenthaler visited and after which she titled three works in our exhibition Helen Frankenthaler. Move and Make.

Altamira, Northern Spain, 1950s.

Contrary to general assumption, not all of Spain is vast (and dry) plains, the North is mountainous, humid, lush, and nearly as green as Ireland. A rugged coastline stretches out to the cold Cantabrian sea, the water is moody grey, the sand warm yellow. It is also one of the least accessible parts of the country, Helen Frankenthaler would have had a long car journey to get to an important yet remote archaeological site, the caves of Altamira.

What made an artist such as Helen Frankenthaler go to visit Altamira, not once but even twice in the 1950s?

The cave’s painted ceilings date back to the Palaeolithic Age (35,000–11,000 BP) and had had its fair share of academic scandal since its discovery in 1879: French archaeologists contested the authenticity of the find by Marcelino Sanz de Santuola (1831-1888), even accusing him of faking the finds. It was only until the discovery of the paintings in the caves in the French region of Dordogne which bore striking similarities to those in Altamira, that the latter’s authenticity was confirmed: the rueful archaeologist Cartailhac published his Mea culpa d’un sceptique in 1902, acknowledging the importance of the find in Spain. [1]

An ochre ceiling, abstract marks in rusty reds and blacks; then these incredibly fine and detailed depictions of bison and deer, using the natural protrusions of the cave to create a near 3D effect. Their quality, in stark contrast with the preconceptions of what Prehistoric humans were capable of at the time, are an uncontested proof that artistic creation started much earlier than previously thought, and was an intrinsic part of human communication.

‘The contour of the ceiling matches the forms of the animals – e.g., big bump on ceiling where [the] bison’s rump is. It all looks like one huge painting on unsized canvas; in fact it all reminded me of a lot of my pictures.’ [2]

So impressed by Altamira, Helen Frankenthaler decided to share her experience of prehistoric art with her newly-wed husband, Robert Motherwell in 1958. During their honeymoon, they first visited Lascaux and then went by car to Altamira. Travelling to that place would, however, not be a necessarily easy choice.

Recovering from a bloody civil war and in the grips of a fascist dictator, Spain tentatively started opening up to foreign tourism in the 1950s. Nevertheless, authorities kept a close watch on visitors from abroad, as many foreigners had supported the liberal government against general Franco, amongst them Robert Motherwell, whose paintings from his Iberia series referenced the previous Republican government. [3] Whilst in Spain, Frankenthaler and Motherwell would have had to be careful not behave in any way that would raise suspicion amongst a steely authoritarian regime.

With little interest in progressive culture, Franco had nonetheless understood that tourism provided a good source of income, so whilst curtailing his own people’s freedom, Franco’s regime worked on showing off Spain’s sunny side. [4]

Clichés such as flamenco dancers, guitarists and bullfighters were pushed as the country’s image to the outside world– you may find that, still today, these are the first associations that come to mind when thinking of Spain. However, the country’s rich architectural and archaeological heritage was equally instrumentalized by the regime as a means of proving that Spain was on the mend.

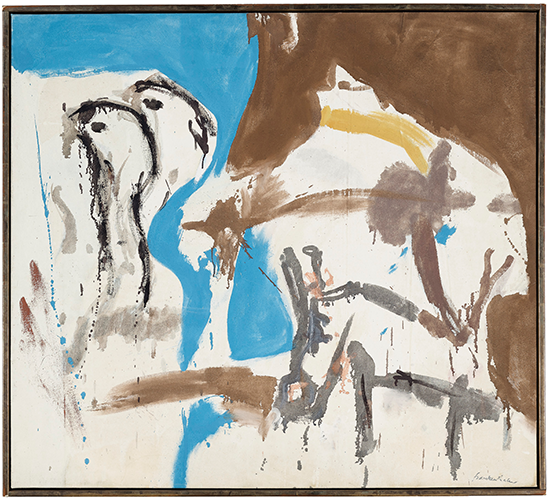

In 1955 alone, over 50.000 visitors flocked to the 300sqm caves to admire the prehistoric paintings. It is unthinkable today and yet tantalising to imagine how Frankenthaler and Motherwell were allowed to visit the caves by candlelight, just after the caves had closed to the public for the day. How those ancient paintings and markings would have come alive with the interplay of light and shadow caused by a flickering candle. The resulting impressions can be found at the mre in Frankenthaler’s early work Cave Memory from 1959.

Altamira itself became a victim of its touristic success. Unfortunately, insufficient climate control and protection led to considerable damage to the ceilings. The caves were eventually shut in 1978 to avoid further decay, opening back in the 1980s with extreme limitations, to then closed for good in 2001. Tourists can visit the facsimile cave, also called ‘Neocueva’, built in the same year using state of the art 3D reproduction techniques, as well as the museum next door. [5]

In an ironic twist of fate, the story of Altamira has also become a story of originality and reproduction: an archaeological find so fine that it was deemed a reproduction, worse even, a fake, becoming later on such a visitor magnet that it suffered irreversible damage, so that the art made by our ancestors can now only be admired via a facsimile.

Your journey through time should end in Santillana del Mar: only a few kilometers away from Altamira, it has a beautiful medieval centre and church. Our trip following Helen Frankenthaler’s travels will take us to Italy next.

Learn more about Helen Frankenthaler’s experience of Altamira in our brand new podcast in German! Subscribe to our newsletter here or follow us on social media to keep track of the latest!

Text: Ines Gutierrez, Museum Reinhard Ernst

With many thanks for their assistance in researching and providing images:

Footnotes:

[1] De las Heras, Carmen and Lasheras José Antonio, ‘La cueva de Altamira: Historia de un monumento’, in La cristalización del pasado’ génesis y desarrollo del marco institucional de la arqueología en España, ed. by Rodriguez, Gloria and Díaz-Andreu, Margarita, pp. 359-368.

[2] Helen Frankenthaler, postcard with detail of Altamira cave paintings, sent to Clement Greenberg from Santander on 9 August 1953; Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[3] https://dedalusfoundation.org/robert-motherwell/artist-timeline/new-techniques-and-forms-increasing-recognition/

[4] Afinoguénova, Eugenia (ed.). Spain Is (Still) Different: Tourism and Discourse in Spanish Identity. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008.

[5] De las Heras Carmen and Lasheras José Antonio, ‘La Cueva de Altamira’, in Sala Ramos, Robert (ed.): Los cazadores recolectores del pleistoceno y del holoceno en Iberia y el estrecho de Gibraltar: Estado actual del conocimiento del registro arquelógico, pp. 615-627.