Summer in Rome can be stifling: there seems to be little respite from the humid heat in the evening. Romans wisely exile themselves to the seaside– the Eternal City is left to intrepid tourists willing to explore its ancient treasures regardless of temperature, while bored stray cats observe them from their strategic placements in the shade. It’s even too hot to beg sightseers for crumbs of pizza.

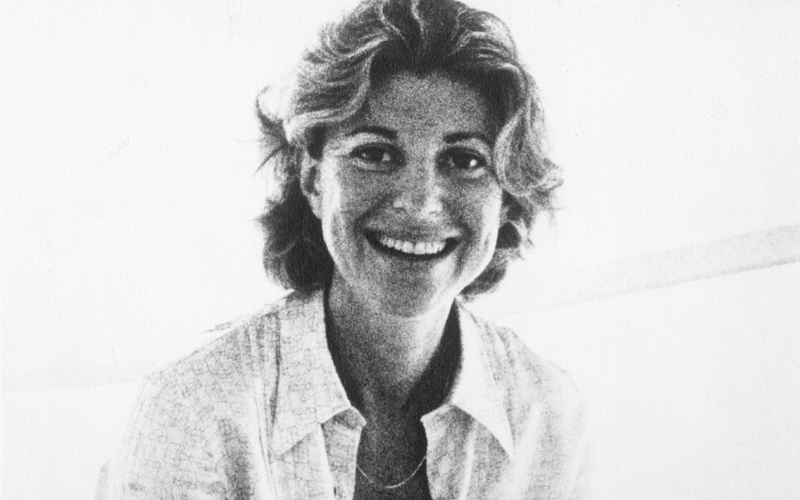

Helen Frankenthaler travelled to Italy twice in 1973, first to Rome in April and then to Ischia in July. Whilst enjoying also some time off during her stay in July, the seventies were perhaps not exactly a ‘Roman Holiday’, neither for Frankenthaler nor for Italy. Following the golden era of the 1960s, where Italy had managed to make a glowing recovery post WWII and put itself back on the international culture map with filmmakers and artists alike (think Fellini, Pasolini, De Sica, Pistoletto, Boetti or Fontana), the 1970s were marked by political and economic unrest.[1] It was also a time of change for the artist, who had divorced Robert Motherwell in 1971 – the so-called ‘golden couple’ of New York’s vibrant art scene was no more.

Frankenthaler immersed herself into her work with renewed energy and turned to travel as a source of inspiration and artistic development. Her trips to Italy in 1973 related to a project with 2RC Editrice, a printing studio in Rome, to work on a group of prints.[2]

Helen Frankenthaler’s stay in Italy was fruitful not only for her prints, but also in terms of painting, completing in the same year a well-loved painting in the Reinhard Ernst Collection: Palestrina.

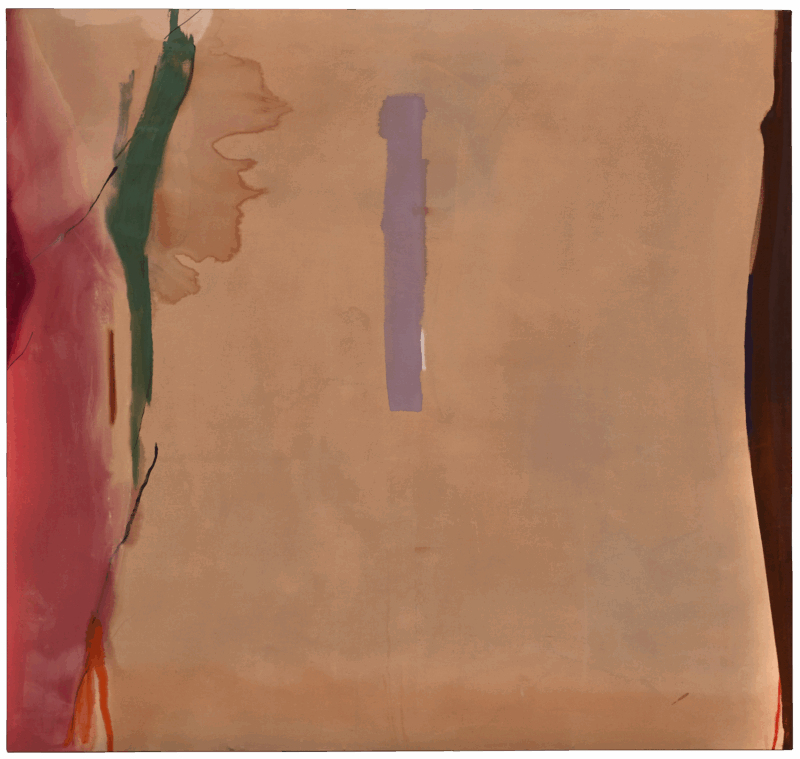

A rather large area of the canvas appears at first glance void, with only vertical strips of colour confining the pictorial space. Yet a closer look reveals an elegantly balanced background, made out of soaking thin layers of reddish beige onto the canvas, providing the picture with a surprising depth. A lilac bar seems to hover above the canvas, slightly veering off centre, as if the areas of burgundy and green on the left side were trying to lure it off key. A contrasting dark brown edge on the right side of the canvas then provides balance and grounds an otherwise rather ethereal composition, where all its elements appear to be held in place by an invisible force.

In a nod to abstraction’s ambiguity, the painting’s title may refer to the Renaissance composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525–1594), a master of counterpoint composition and church music, or to his actual birth town, Palestrina. Historically known as Praeneste, it is located near Rome, and back in the 2nd Century BCE boasted one of biggest temple complexes in Antiquity.[3] While it is indeed tempting to link the colour palette with the dry plains stretching from Palestrina towards Rome in summer, or the burnt red tiles of the town’s roofs, it is not known whether Frankenthaler actually visited the site during her stays in Rome. However, examining this extraordinary place does nonetheless reveal interesting parallels to Frankenthaler’s practice.

Dedicated to the goddesses Fortuna Primigenia and Isis, the history of the temple brilliantly illustrates how foreign cults and beliefs travelled throughout the Roman Empire, permeating and transforming its social fabric, and in many ways foretelling our own culture’s malleability through globalisation. How does the Egyptian goddess of fertility and creation make her way into a temple in the heart of Italy? Did the Romans themselves not have a large enough Pantheon to pray to for their offspring and fruitful crops?

When Alexander conquered Egypt in 332 BCE, some of the Egyptian cults were introduced into Hellenic culture as a way of brushing over differences and creating a common base of beliefs between the colonised regions and their colonisers. Isis had her counterpart in the Greek goddess Aphrodite, yet she had more powers and seemed to be a key figure for Egyptian women. A similar approach of religious tolerance within limits was adopted by the Roman empire. Initially reluctant to adopt foreign traditions brought over by Greek and Egyptian migrants, it was only during the emperor Caligula’s reign (37–48 CE) eventually gave into officially permitting the by then quite widespread albeit somewhat illegally cult of Isis. Temples were therefore built, Palestrina being one of the most important in that context.[4] Of course, Isis could not have a temple all to herself, so in Palestrina she was allowed her place next to the Roman goddess Fortuna Primigaenia, (the firstborn), meaning that this large sanctuary was entirely dedicated to motherhood.

Unlike in Cave Memory (1959), Frankenthaler’s Palestrina does not provide any visual links to the place or archaeological site. However, her soak-stain technique transcends the mere artistic practice and reminds how in History no society successfully grows and evolves in isolation. Frankenthaler’s way in which canvas and colour become one, transforming in the process, letting a new reality emerge, echoes how communities can accept outside influences to enrich its own social fabric, in Ancient Rome and now.

Perhaps any trip to Rome should indeed include a little outing to Palestrina. Off the beaten tourist track, the breathtaking views from the temple, as well as the Nile mosaic in the Palazzo Barberini (now Palestrina’s Archaeological Museum) are certainly a worthwhile sight. There’s even a late Pietà by Michelangelo in the Cathedral, to make up for potentially missing out on the Sistine Chapel.

The last stop of our whistle tour following Frankenthaler’s journeys will take us to the US in September: do subscribe to our newsletter or follow us on social media to keep track of the latest! You can also find out more about the artist in our Podcast (in German): Frankenthaler – available on all platforms.

Text: Ines Gutierrez, Museum Reinhard Ernst

With many thanks for their assistance in researching and providing images:

Further reading:

[1] Renato Caputo, ‘Gli anni Settanta e Ottanta in Italia’, in: https://www.lacittafutura.it/unigramsci/gli-anni-settanta-e-ottanta-in-italia , published 01.07.2022, page visited: 11.07.25.

[2] Harrison, Pegram, Frankenthaler: A Catalogue Raisonné. Prints 1961–1994, Harry N. Abrams Inc. Publishers, New York, 1996, entries 42–44.

[3] J. Champeaux,’Le culte de la Fortuna à Palestrina’, BStorArt 29, 1986, pp. 26–30.

[4] Valentino Gasparini, The introduction of the worship of Isis in Rome’, in: https://www.archaeologie-online.de/tagungsberichte/athens-and-rome-introducing-new-gods/the-introduction-of-the-worship-of-isis-in-rome/ , published 14.1.2008, page visited: 09.07.25.